A Patient, The Police and A Priest

He turns up in the morning rain, without a jacket, carrying a sleeping bag. All wet. I don’t

have much time. A funeral is about to begin. He looks pleased and I’m pleased to see him too

even though he shouldn’t be here at all. Shouldn’t be out, having been sectioned for twenty eight days a couple of weeks ago. He said they gave him leave. I give him bread, cheese, coffee

and milk and send him to the hall where he can have shelter. A bit of privacy. And a smoke

by the open door, thanks to the kindness of Terry. I put his sleeping bag in the dryer.

A few hours later when the funeral is over, I get myself some lunch before going to check on

him and phone a relative of his to see if the family can do anything to help him. They can’t.

The phone rings. It’s the police. Missing persons. Had I seen him? Yes, in the morning. He

needs to go back.

Phone rings again. The hospital this time. They’ve been informed by the

relative that he’s “with” me. He was, I say. I’m told in the strongest, blunt terms how serious

this is, how dangerous - as if I were somehow to blame. I take it on the chin. But later think to

myself that it is they who let him escape, not me. Of course it's worry that makes a person talk like this. It’s clear to me that the patient needs psychiatric help

and he was in a secure unit because he attacked someone. The nurse on the phone tells me

that 999 has to be called and, to be fair to him, he offers to do it for me, knowing that there are

issues of trust between me and the patient. When he was arrested two weeks ago, he gave

them my name as his contact.

I’ve seen his distress, the wild thing that goes off in his head, making him see reality in a way

that I can’t see it. We see and experience the same reality in very different ways. But he has

never been a threat, never intimidating, even though he’s a big strong man.

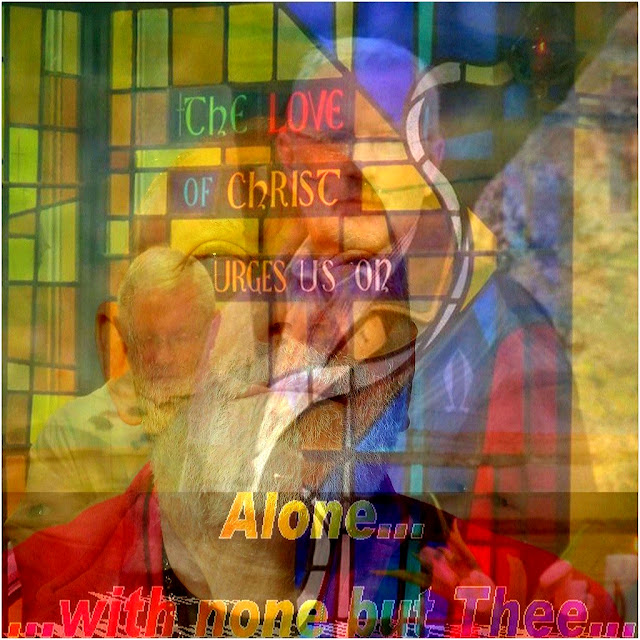

The large crucifix upsets him because he sees Jesus alive and moving on it, sees Him suffering

and so he feels compelled to take the cross down so that Jesus can rest.

After the call from the nurse, I go back down to the hall and talk to him about the need for

him to return to the hospital but it frightens him. He’s sorry but is afraid of returning there.

And I’m conflicted, torn between my loyalty to him and my obligation to the civil authorities.

The need to obey those in power is very strong in me, like a survival instinct, one that has to be

challenged because it risks surrendering the weak to the strong, the helpless to the powerful.

He won’t be persuaded and, in some way, he now becomes the authority that I am willing to

obey, need to obey. I have seen plenty of times how vulnerability can turn from being a grace

into a way of exercising power. What is necessary is to do what is right, regardless of either

power.

“I love you to bits” he says, hugging me as I leave him again. “I love you too” I say. He walks

about happily in the new Sketchers that Mary bought for him, wearing a rain jacket he found

in one of the stores off the hall.

Back in the house, the police phone again and, with a pang, I tell them where he is. Then I go

to the church to watch and wait and pray. It’s the hour of mercy. He emerges from the hall

and tells me he’s leaving. I tell him that the police are looking for him and that they will

eventually find him. It will happen tomorrow he says.

Ten minutes later the police ring at my door. Two squad cars. Two men and a

woman - each one very pleasant. They’re not a threat. I have an idea where he’s going and tell them. They’re afraid he

might get agitated and ask if they can use my name to calm him. I said no because it might

damage the bond between us. My answer is accepted and I tell them too that I’ve never felt

under threat from him. He’s usually calm with me.

They don’t find him. This I know because I bump into him while out walking. Says he’s going

to sleep in a hut near one of the old lifeboats but later he walks past me at speed, accompanied

by a young woman, so, a little concerned I decide to phone the police to tell them I’m looking

at him. As with every modern phone system I’m put on a queue, being apologized to time

and again for the delay. They’re very busy at this time. Twenty minutes later I hang up

because he’s well out of sight.

Next morning, I spot him from an upstairs window walking down our street, carrying his

sleeping bag. My heart goes out to him but still I feel obliged, for his own sake, to call 999 and I’m dealt with

more quickly. Later, I find his sleeping bag in the church lobby but of him there is no sign.

I’ve gone out looking for him and return each time to find his sleeping bag still there. Still

there when I lock the church at the end of the day. And I pray for him wherever he may be. And wonder will he know that I'm to blame if he has been found.

It's more than a week later now and he has phoned me a couple of times from the hospital. A woman from the parish was outside the church when the police came for him. She recognized he needed help, encouraged him and escorted him to the van.

He said they have taken all his clothes, so I phoned the nurse in charge who told me that J could do with clothes and when I asked his advice on what to get, size etc, he said, "Here I am, a 49 year-old man talking to another man about clothes!" It was said nicely. So, without his advice I decided to go shopping for new clothes rather than going to a charity stash somewhere. And I'm glad I did because, when J received the parcel he phoned me with the delight of a child. The idea of having new clothes made him so happy. He said, "now I can be warm for the winter and I can go to one of your Masses."

So, that is a little lesson to me - how difficult it is for the poor to come to church; how important is the dignity of new clothes.

It was said to us at a Jesus Caritas retreat recently, "the clothes in your wardrobe and the money in your bank account belong to the poor." It paraphrases the teaching of some great Saint whose name I've forgotten but it's the message that matters. I haven't forgotten and must never forget the message. So, anything I have done, am doing or will do for a materially poor person is simply giving them what is actually theirs and there's no credit due to me at all then. And I am so enriched by my encounters with them, most specially by our mutual loving.

It's more than a week later now and he has phoned me a couple of times from the hospital. A woman from the parish was outside the church when the police came for him. She recognized he needed help, encouraged him and escorted him to the van.

He said they have taken all his clothes, so I phoned the nurse in charge who told me that J could do with clothes and when I asked his advice on what to get, size etc, he said, "Here I am, a 49 year-old man talking to another man about clothes!" It was said nicely. So, without his advice I decided to go shopping for new clothes rather than going to a charity stash somewhere. And I'm glad I did because, when J received the parcel he phoned me with the delight of a child. The idea of having new clothes made him so happy. He said, "now I can be warm for the winter and I can go to one of your Masses."

So, that is a little lesson to me - how difficult it is for the poor to come to church; how important is the dignity of new clothes.

It was said to us at a Jesus Caritas retreat recently, "the clothes in your wardrobe and the money in your bank account belong to the poor." It paraphrases the teaching of some great Saint whose name I've forgotten but it's the message that matters. I haven't forgotten and must never forget the message. So, anything I have done, am doing or will do for a materially poor person is simply giving them what is actually theirs and there's no credit due to me at all then. And I am so enriched by my encounters with them, most specially by our mutual loving.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment